And so we embarked on our voyage along the coasts of Bohemia, inspired by pan Lva z Rožmitálu.

A rather difficult task, as this is a completely landlocked country. Those ponds you see everywhere? Man-made creations devised for irrigation and keeping carp fresh until Christmas.

My friend lent me his time machine, and we could not resist taking a journey to the old country, the origin of 1/4 of my soul. Unfortunately, his device proved to be a bit, well, unexpected.

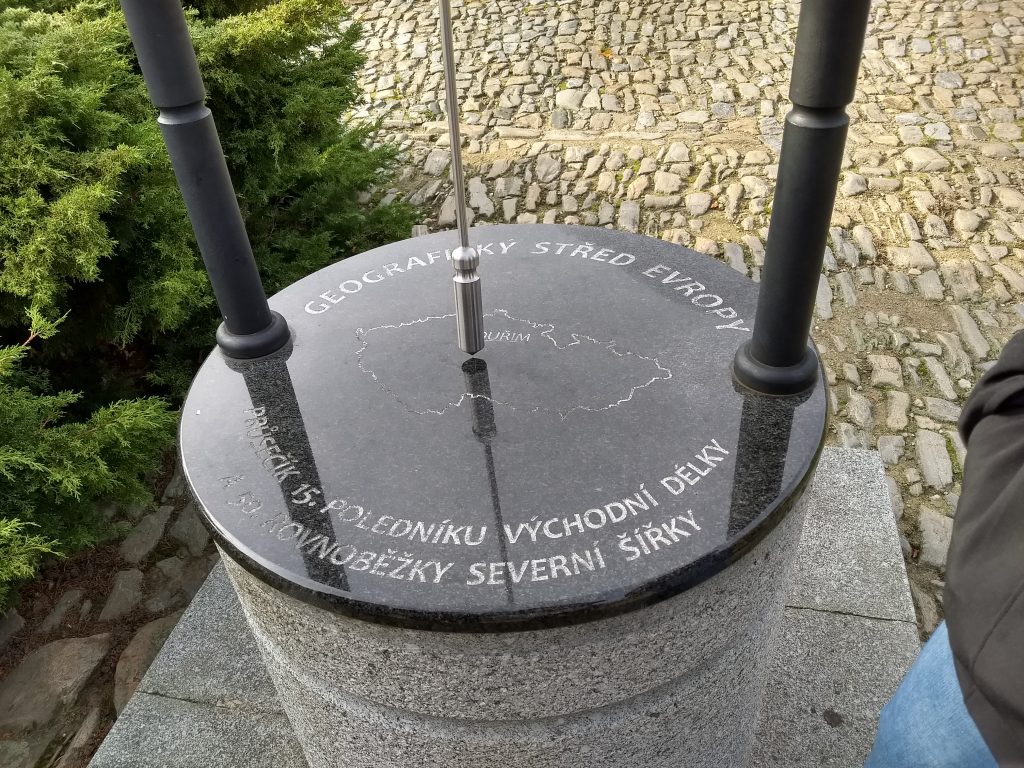

Forget that part about the “coasts.” We actually started our trip in Kouřim, the geographical center of Europe. We started our trip on 6 November 2017. This is actually where we met my friend with the time machine, in this village square.

He lent the thing to us, firmly pressing a scrap of paper with the exact coordinates and time settings for our return, which was to be set exactly 30 seconds into the future in his time. I was too excited to think very carefully about that part. I was finally going to accomplish my dream and travel back in time in the old country.

He pulled out a rickety looking hunk of metal that looked like an ordinary tandem bicycle with two large 2-liter soda bottles duct-taped to the frame and a few dials and knobs on the handlebar. Before we had much time to scratch our heads, he explained how the thing worked. Easier just to show it.

As usual, I was extremely anxious to get going, and my thoughts were completely elsewhere as my friend explained the details of how to run it. I figured it was something that could be figured out as we went.

How very wrong I was.

My husband did his best to listen, but he doesn’t speak Czech, so…

It turned out that while the device was powered by human pedaling, my friend had set some kind of lever which made it so the machine sent us to a random date in history if we stopped pedaling for more than 30 seconds and were still sitting on the seats.

And so, that is how my very obliging beloved and I set off on our journey across time and space through the historic lands of the modern Czech Republic, one village at a time.

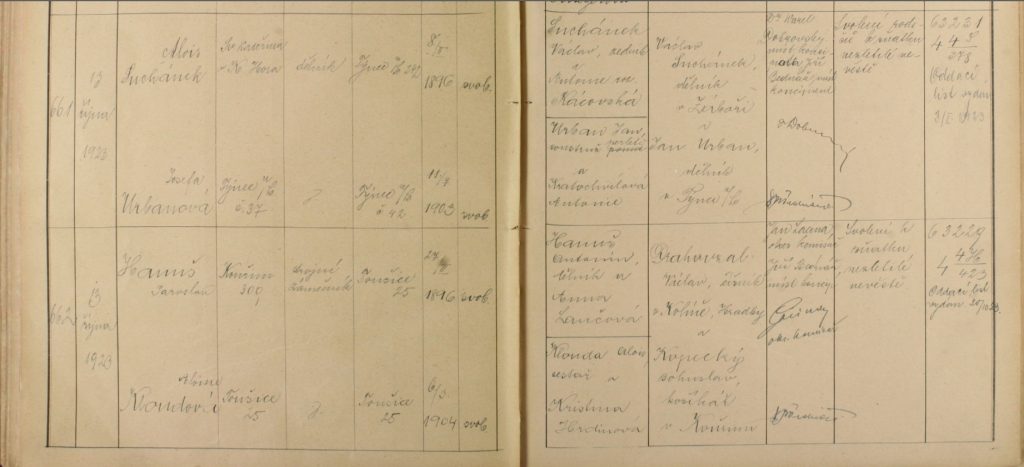

Our first actual stop was in Toušice on 13 October 1923, a nice little village. We attended the wedding of a nice guy named Jaroslav Hanuš and his bride, Aloisie Klondová. She whispered that she was a “nezletilé nevěsta”, aka an underage/minor bride. She was 19, not really so young as all that. Heck, in the states, the age of majority was 18.

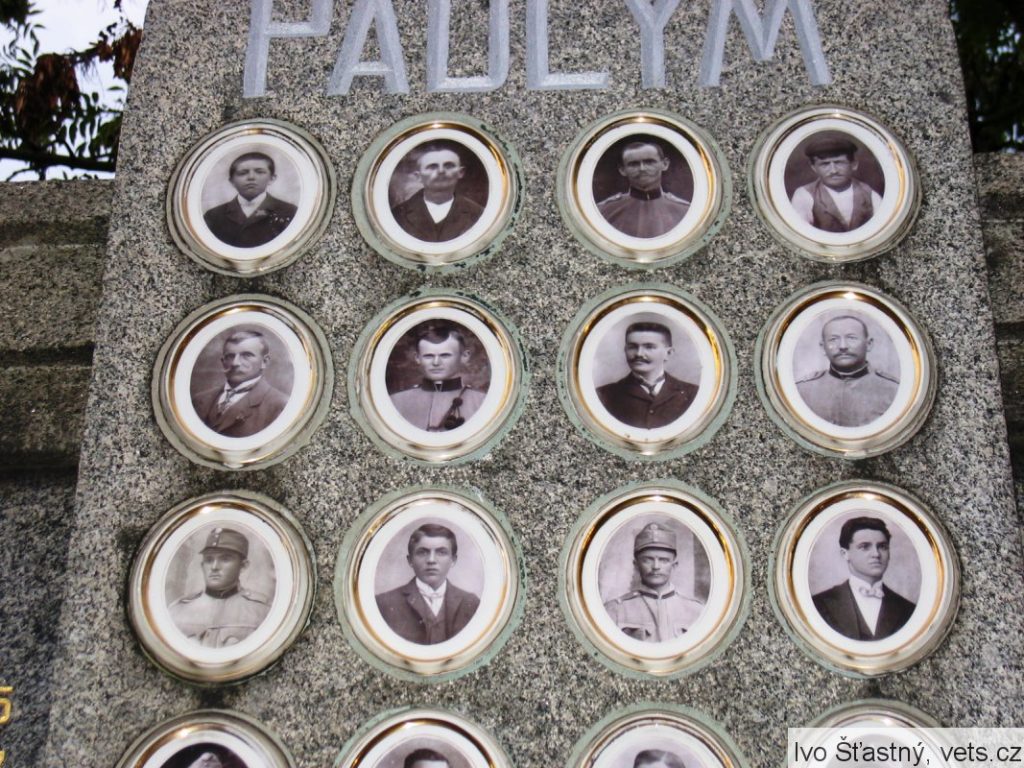

Svojšice on 28 September 1921 was our next stop. Careful, there are a couple of these throughout the land. This one is in okres Kolín. We saw a solemn crowd gathered in the center of this small village as a stone monument was unveiled to commemorate the 19 men from this village who fell during the Great War, along with another 10 from neighboring Nová Ves. A man named Bohuslav Šimek from the neighboring village, a teacher, gave a sad speech but frankly, most of the citizens were not listening very carefully. The war had been “won” four years earlier. The girls who had once dreamed of marrying these young men were now married and pregnant, some with several children. It wasn’t that they didn’t care; in fact, surely they did. Some of them had been their brothers. It’s just that life went on. It had to go on. Every village had been affected by this devastating and insane war. If you stopped to think about it too hard, you would go mad.

We then went to Krychnov, in the middle of the night on 10 June 1626 (though to be honest, I didn’t really look that closely at the dial settings, as my husband was steering this time). It was odd that the machine would send us to this place in the middle of the night. There were a few small huts with some muffled noises coming from them – probably animals – but it was mostly just completely silent.

Then, we heard it.

Scrape, scrape. The sound of a shovel digging. We decided to investigate more closely. Carefully hiding our machine in small bush by the side of the dirt path (it was a path, right? It was actually pretty hard to tell), we walked carefully in the dark towards the sound. We were able to get close enough to catch a glimpse of someone digging a hole. He looked extremely nervous. We wanted to see what he was burying. We hoped it wasn’t a body.

It turned out to be a clay pot.

I really wanted a closer look, but I didn’t dare get any closer while the man was still there; no cover. We waited for about half an hour, until the nervous man snuck off. We noticed that he took care to walk in a straight line towards a nearby large tree. He was probably trying to memorize where he had buried the clay pot so he could unbury it in the future. Intriguing.

We waited an extra ten minutes to be sure he wasn’t around. We ran over to the spot in the field where he buried his pot. It was easy to dig it up again.

We opened the lid of the clay pot and found it to be full of treasure. Gold and silver gilded challices each brimming with coins – so many coins! Silver and gold minted coins, of incalculable worth by 2017 standards. For a short while we debated about whether to take them back with us, but decided they were too heavy. You know, and we didn’t want to alter the space-time-continuum. We reburied them, taking care to dig them down an extra few inches to help the guy out.

We wondered about who he might have been. It was the end of the Thirty Year’s War, so maybe he was a Burgher who was fleeing from the destruction and chaos, and simply couldn’t take his treasure with him. This seemed unlikely to me. Who would bury such a vast amount of treasure? More likely, in my opinion, it was stolen by one of the traveling mercenaries who literally could not have hidden it from his superiors. Perhaps he figured that after the war was over, he would return and find it again.

Well, it turns out that this Krchnovský poklad was eventually found…in 1930 by a farmer plowing his field. Sometimes a small portion of the coins which remained are on exhibition. The oldest remaining coin is dated 1575, the youngest 1625.

Our next stop was Libodřice on 15 July 1641. Václav Rudolf Strella was so very hospitable to us, offering us a tour of his newly inherited castle (as well as a delicious lunch of bread, blood sausage, and some dubious looking homemade cheese). Really, he explained to us that it wasn’t that newly inherited, he had been there for the past three years. But he finally was getting around to some long-needed updating. “When you own a 150+ year old home,” he said, “sometimes your priorities are just purely practical.” We nodded and mentioned that our neighbors had the same kinds of problems in their home in rural Iowa. Previous owners had basically jerry-rigged the indoor plumbing. He was quite friendly and we talked at length about how he might update the kitchen and hallways by adding some brick archways.

After 2011, part of Rudolf’s castle was demolished and reconstructed, but you can see how we helped inspire these open arched ceilings. Hey, it is stylish even today!

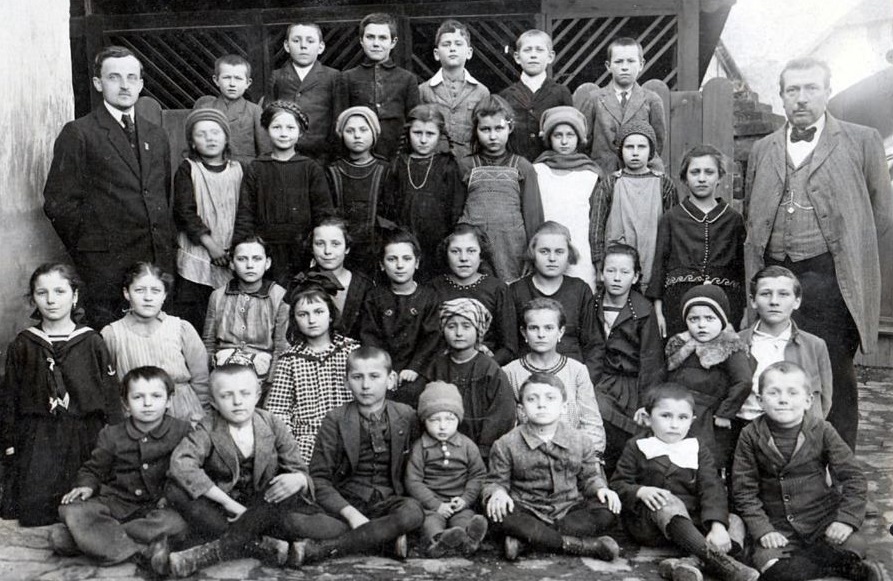

Our next stop was Polní Voděrady on 10 September 1923. A photograph was taken of the students with their teacher Jaroslav Procházka (on the left), and it was quite amusing for us to watch. First of all, the kids found it quite difficult to keep still. Second, the man behind the giant box of a camera was making ridiculous faces. “I can wiggle my ears!” “Can not!” “Yes, I can! I will prove it! But you must look very closely.” This got the children to look intently at the photographer. Weeks later, the little boys would go home to their fathers and beg for them to buy a copy of the photograph, to which the fathers would respond, “What do you those teachers at that school of yours think I’m made of? I haven’t money to waste on frivolous and wasteful things like photographs!”

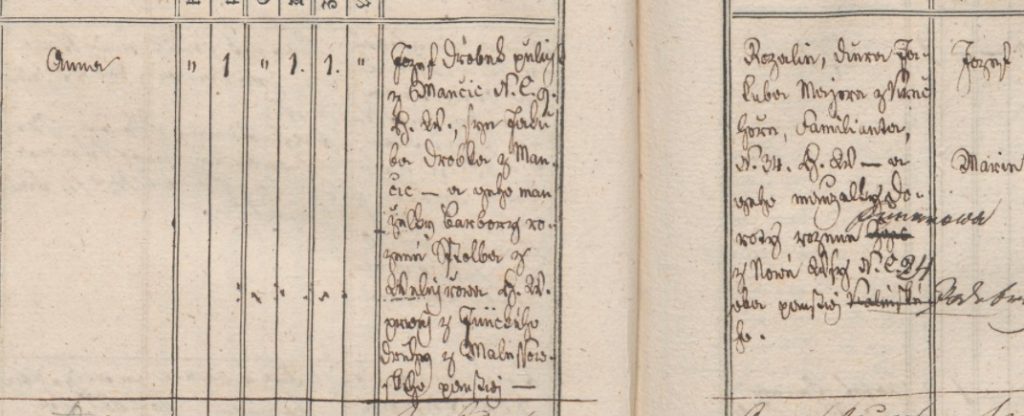

In Mančice on 3 June 1839 Anna Drobková was born. She was baptized the next day. Her mother Rozalia Majová had been born Jewish – actually, with Familianten Number 34, but she had married her protestant husband Josef Drobek. They told us they were planning on having baby Anna baptized the next day. Protestants were not equal with Catholics, so perhaps this was one reason why Jozef had married Rozalia; perhaps they could empathize with each other. Rozalia’s marriage was probably difficult for some of her family to take, because it meant marrying outside the covenant. All through the Torah are warnings about how important it is to marry within the faith. But if she hadn’t had the opportunity to marry someone with a Familianten Number, she would have either had to live in sin without the spiritual or legal benefits of a marriage contract or find a gentile husband. We thought it was an inconvenient time to ask them such an impertinent question.

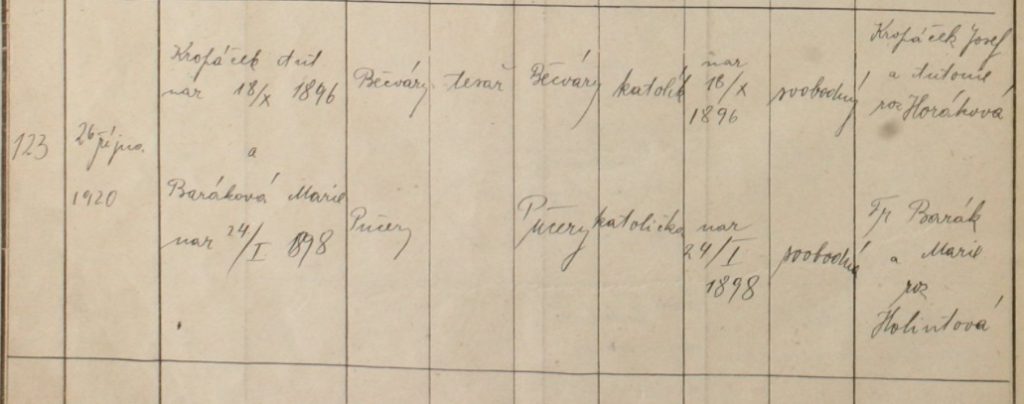

In Pučery on 26 October 1920 we found the bride Marie Baráková with her groom Anton Kopáček sitting at a long table at one of the main village inns. They were tied together with a ridiculously enormous white tablecloth for a napkin and were in the middle of eating some delicious hovězí polévka s játrovými knedličky (beef soup with dumplings) out of one bowl with one spoon, as a symbol, of course, of how they would have to work together in equality to make their marriage work. My beloved said, “I wonder if they have the same associations we have with our cake tradition, and how messy it is.” I raised an eyebrow and said, “Probably not. This is civilized Europe, not Hickville, USA.”

Then we came to mid-1628 Chotouchov, a place which was directly influenced by the decisions of a slimy Flemish man named Hans de Witte. When we got there, the village lay in ruins. Fields lay fallow or half-burned. It was really awful to see. Abandoned barns and houses, and the eyes of starving farmers and their malnourished wives and children, staring flatly at us. Partially because of the greed and scheming of Hans de Witte, inflation had risen to an astronomical amount. Money had lost its value. These villagers had no knowledge of Pan de Witte, who was at that very moment in a far away town, purchasing this village along with several other neighboring villages in nearby estates.

Eventually Hans de Witte became so in debt that he had to go into more debt in order to make payments on his original loan. He was dealing with the equivalent of billions and billions of dollars.

I wonder what the citizens of Chotouchov would have thought if they had had a crystal ball and could see that in just two short years, Hans de Witte would see no way out of his financial mess of borrowing, refinancing, and paying interest with more debt and finally decided that he should take his life.

Hans de Witte was one of Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von Wallenstein’s financier, but because I couldn’t find a good picture of him, I just used one of his boss. (By the way, Wallenstein was not a man to be trifled with. A very, very scary, powerful man during the Thirty Years’ War, which you can watch in all his terrible glory here.)

We were a bit surprised when we jolted into Malenovice in the year 1436, because we almost ran over a group of nuns walking down the road. Which, by the way, could hardly have been called a road. After apologizing and asking for directions to the village, which looked completely unrecognizable by the way, we stopped to chat with them. They told us the latest gossip, about how their village along with neighboring Miletín were probably going to be sold. Apparently some of them had somewhat strong feelings about this. I couldn’t really make out why. Other than that, they were happy to talk to us about their vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. I found it really interesting, and they were quite pleasant to talk with.

Check out the stylish fringe on these medieval nuns’ habits.

That’s all for the most recent time-traveling adventures. It seems to take me a little bit more time to write it all down than it does to actually go there, for which I apologize. For example, we have already traveled to Sedlov, Ratboř, Pašinka, Polepy, Kolín V, Borky, Hradišťko, Veltruby, and Velký Osek by now, but I have yet to write about our adventures there. You would think that a time machine would give one more time to write, but it seems that the opposite is true: the more opportunities I have to learn and travel, the less time I have. What messy, paradoxical stuff this time-traveling business turns out to be.

1 thought on “Cesta z Čech až na konec světa: část první”