For the first part of this series, see část první here. If you don’t want to bother with that, the gist is that my husband and I are riding a time traveling bike across the Czech lands. We started in the geographical center of Europe in Kouřim and have not stopped since.

On 3 May 1653 we found ourselves in Sedlov, or more appropriately, what had once been Sedlov. What we saw looked more like a piles of rocks, the ramshackle remains of house foundations. Many had been burned, and posts which were black with ash stuck up from among them every once in a while. We saw fallow fields full of weeds blowing softly in the wind. Random bones of animals (well, we hoped they were animals!) peaked out of the grass.

“Sir, can you point us in the direction of Ratboř?” we asked to a man standing and watching us warily from his house, which would never have passed modern inspection standards. I was hoping to assure him that we weren’t enemies, that we were just travelers passing through. This seemed to put him at ease. Because it was evening and it was getting dark, he let us into his small cottage where his scrawny, quiet wife fed us a bowl of thin soup. We found out that his name was Jíra Krulich and that he and his family were literally the only inhabitants remaining in the village after the Thirty Years War. This sounded rather lonely to us. We wished him the best.

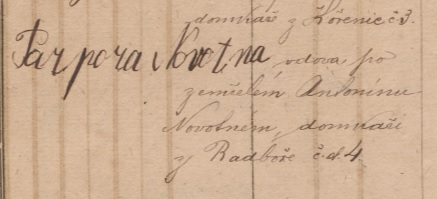

Next stop was Ratboř on 12 December 1891 where attended the baptism of Marie Novotná. We learned that nearly everyone in this village and the neighboring village of Kořenice is related somehow to the Novotný family. Colloquially people have started identifying various branches of the family with different adjectives, though officially none of that has been written down in the matriky books yet. Marie Novotná and Barbora Novotná signed as witnesses to this baptism on this cold, snowy day.

On 5 June 1890 in Pašinka we overheard quite an embarrassing conversation between a father and a son in the courtyard of a rather wealthy looking house. It was a lovely afternoon and the birds were singing in the trees, but meanwhile male shouts could be heard from the street. An older man was shouting at his son. “Venco! I forbid you to leave! I utterly forbid it!”

“Father, you know you can’t stop me. I am my own man! I intend to make my own way in this world and there is nothing you can to to stop me.”

“But I just know those French painters will utterly corrupt you.”

“Father, you know that France has always been the center of the art scene. I just have to be a part of it! Just think what I could do, what I could become! With a little training, I’d – ”

“Hang the training! You should have followed me into the law. What a disappointment you have turned out to be. Just one giant disappointment after another.”

“Father, I -”

“Not one kreuzer will I send with you to chase after foolish dreams.”

“Father, if you’d only -”

“No, Venco. You are giving up the life your mother and I labored and toiled to give you, all for some foolish art dreams.”

“How dare you bring up mother! Or have you forgotten her dreams for me? How it was she who taught me to draw in the first place?”

“And what become of your inheritance from your dear mother! Squandered away in Vienna!”

After a few moments, the young man angrily stormed passed us, slamming the iron gate behind him. He looked like this:

Then we found ourselves in Polepy on 10 September 1382 where we met Petr Krautwurst as he was on his way to found a new mill. “I’ve always been an entrepreneur,” he said. “My great grandfather, a good Saxon, taught me all kinds of tricks of the water mill trade. I figure that these Bohemian peasants aren’t much competition, and so I can build a pretty good business by moving on.”

“So, you just sold your technology, just like that, to a Bohemian?”

“Bartík? Aw, I like him. He is a good guy, a hard worker. Yes, I sold him the mill.”

“And you aren’t worried of him stealing your secrets?”

Petr laughed. “Running a mill is hard work. Ours was the best for miles around. You see that big wheel? the water runs down the stream and turns it. The cogged teeth turn that next smaller wheel, and the water from the troughs – we call those lamfešt – flows into the buckets on the driving wheel and weighs them down so much that the wheel starts to turn. That causes the cévník on the other side of the wheel shaft to turn, and it is, of course, fixed on a vertical shaft of metal. That is where we install our grinding stone. It is really not too complex of a design if you think about it. Somebody was bound to figure it out eventually.”

I stared at Petr.

“We can process over a bushel of wheat in one hour. Think of what that could mean for these poor peasant villages. All the villages around here have some kind of stream running through them. If I travel just over that hill, and offer a wealthy burgher if he would be interested in starting a new mill, I am quite positive that my reputation for excellence will have reached his ears and he will be overjoyed to put down solid money – and room and board – while we execute the project. This technology could change the world. It is simply fantastic. And I wouldn’t even mind selling my ideas to a Jew, if he could pay, of course.”

I tried to look surprised, as if the thought of doing such a thing was something unheard of.

Meanwhile, Petr’s son was smiling at us, as if to say, there he goes again, on and and on about his dreams. He did seem proud, however. He showed us a few flour sacks in his hand. Some of them were really loosely woven. “That’s for the coarser flour. These ones here are for the finer flour. But sometimes they cause problems in the machine. One time -”

“Son, they best be on their way, don’t you think?”

As we started biking away, I told my love, “That guy is really ahead of his time, don’t you think? I mean, besides the antisemitism.”

“I guess the entrepreneurial spirit is timeless. And his opinions towards Jews were pretty forward thinking, too. I mean, weren’t entire communities of Jews being murdered and massacred at this time in Bohemia?”

I nodded. “Yeah, I guess that is true. But still…”

We popped into Kolín during the middle of what felt like a surreal nightmare. It was the night of 24 August 1944 and we could hear sirens blaring the warning of an air raid. A wave of allied airplanes zoomed overhead, dropping bombs. We were confused; the bombs landed in an oat field. Surely that was not the target!

We quickly hid ourselves behind some trees. A second wave flew in and dropped at least ten bombs. These also mostly missed hitting anything significant.

But one airplane, which had clearly sustained some damage, hit a building which immediately went up in flames. A dense, black smoke began to rise, driven east by the wind, filling the fields near where we were hiding. The owner of the fields started to yell to someone, “The factory! They’ve bombed the factory!”

We watched and saw as the bombs continued to fall. By now the bombs had completely destroyed some kind of chemical reservoir attached to the factory, as well as the adjoining buildings. Then some kind of clerical building. Then a train station. Then the train tracks. You could barely hear the screams because the air was filled with the roar of the planes and the blaring of the sirens.

Eventually things calmed down. The owner of the field had found all the members of his family, and all were safe, though one of them had been in a haystack which was still ablaze from the bombs which had destroyed the field. We offered to help them put out the fire with some heavy leather blankets. While doing so, we heard the father and son exchange frantic whispers.

“Papa, what are we going to do?!”

“Well, at least we planted oats – we harvested a few weeks ago. We’ll be fine.”

“But the factory, papa! We all depend on it so much!”

“You mean the Nazis depend on it so much. I wonder where they will get their supply of Zyklon B now.”

Next stop was Borky, a little area that is a suburb of Kolín. We arrived on 3 June 1949, about a year and a half after the creation of Základní kynologická organizace, the kennel club for Kolín area. My love was totally shocked at the passion and devotion these people had for their dogs. I mean, it is easy to start a project or an organization. There is momentum and initial interest in anything. But nearly all the members of the original group were still there, with their dogs. This included both men and women, among whom were pan Oldřich Slepička, pan František Červenka, paní Jana Stará and paní Marcela Ulcová. There they were, dogs on leashes, sipping some coffee and discussing breeding methods, the upcoming lecture by a local professor of veterinary medicine, and the ethics of dog racing. When we asked them about funding for their organization, they were a little bit shocked. I think it might have been in bad taste to be so forward and open with our concerns, but seriously, in postwar Europe, their democracy had just been annihilated by the occupying Russian forces, and there they were, worrying about…dogs? But paní Ulcová eventually responded by saying, “I do not think we have much to worry about. This is a nation of dogs and dog-lovers. Other places might struggle for financing under such circumstances, but dogs have always been an important part of Czech culture, and will always continue to be so.”

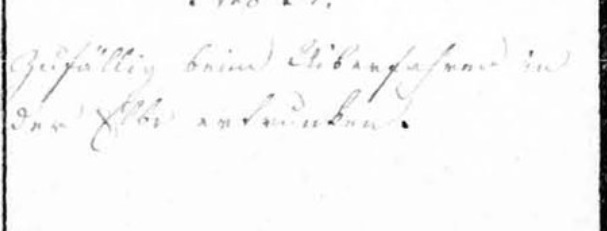

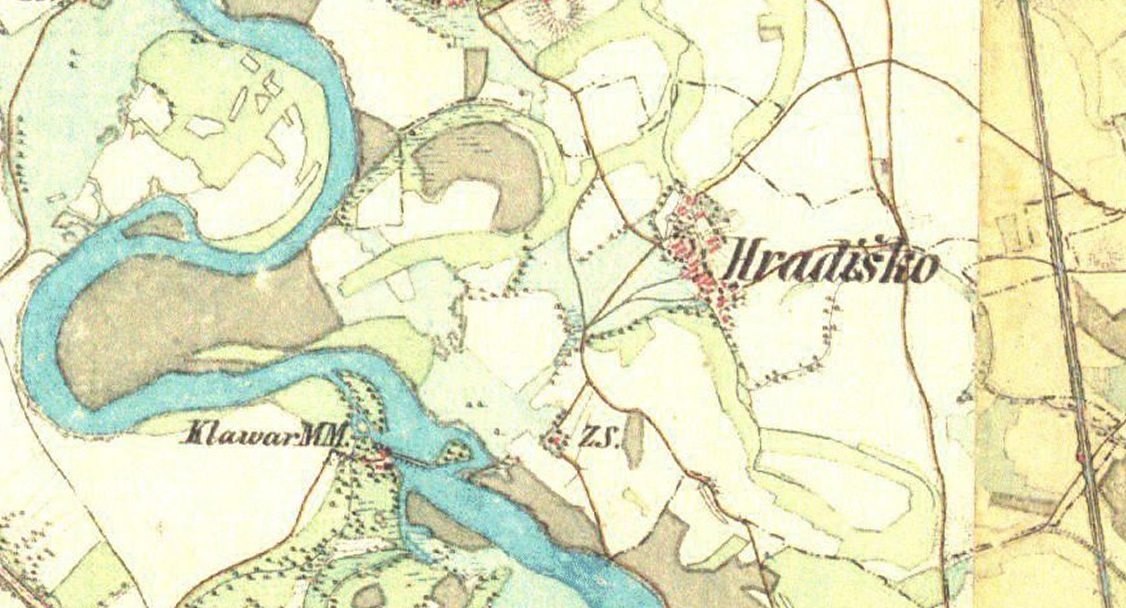

Next stop was Hradišťko on 18 October 1839, where we met Franž Kasik, chalupník and rychtář of the small village. He was just leaving the parish office, his head down and face grim. “This seems to happen every year,” he said. “Poor old Kateřina. She was just ferrying across the Elbe, when she slipped into the water and was washed away. We couldn’t find her for over a fortnight, and when it was found, it was so far downstream it was almost unbelievable. They called me in just now to the márnice as a witness that it really was Raimanová, and unfortunately, it was. And so I had to sign the paper in the parish office. Her poor family is devastated. The burial and mass will be tomorrow.”

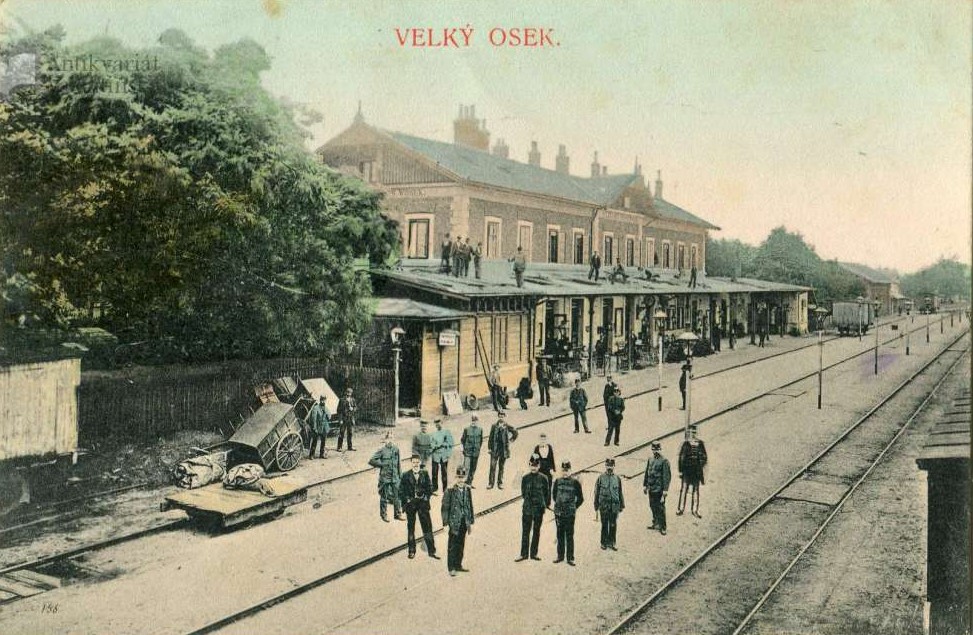

Our last stop was the train station at Velký Osek in October 1936, where we met Pan Ředitel František Chvála. He was on his way to a holiday at one of the spas near Poděbrady. When we asked him how he enjoyed teaching, he went on a fantastically detailed tyrade about how the children of Velký Osek do not know how to work. “They don’t know how to work at all, and I mean, even the slightest little amount of work – this is not something they are accustomed to doing. And why? Their parents do not make them work at home and they have never worked in the garden! I noticed this when we were preparing the school garden. The pupils were completely ignorant of what to do and mounted a terrific resistance. And the parents! They are not on my side in the least. They just let their children play and scream and when I remind them about the importance of homework, they just shrug their shoulders and say something like, “kids will be kids.” Strict verbal reproaches do not work. And in the end, who do these foolish parents blame for their children’s continued ignorance – me! It is absurd!”

We supposed that he really deserved that vacation to the spa, and waved him goodbye on his train.

Next stops: Oseček, Sokoleč, Poděbrady, Odřepsy, Vlkov pod Oškobrhem, Libněves, Žehuň, Choťovice, and Žiželice.

Until then, sbohem!