When analyzing old Czech records, expect certain letters to be interchangeable. For example, there wasn’t a distinction between v and w. I have heard Texas Czechs from my grandpa’s generation say, “Vesele Walentine’s day.”

Here is an example of a text that uses j, ý, y, i, and í almost interchangeably.

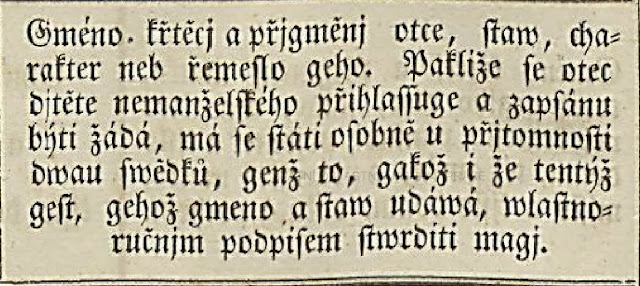

This is from a baptism parish register from 1859 in Sýkořice. This is the subheading under the Father’s half of the “Parents” heading.

The first step in transcribing is to write exactly what you see. This was my first attempt:

Jméno. křtěcj a přiyměni otce, stav, charakter neb řemeslo jeho. Paklíže se otec djtěte nemanželského přihlassuge a zapsánu břjti žádá, má se státí osobně u přjtomností dmau svědku, genž to, gakož í že tentíž gest, gehož jmeno a stav udává, vlastnoručnjm podpísem stvrdítí magi.

Google translate tells me that I still have some work to do. Here is the first translation. I bolded the words that stood out as incorrect.

Name. křtěcj and přiyměni father’s condition, because the nature of his craft. IF the father of an illegitimate djtěte přihlassuge a registered břjti asks the person is standing at přjtomností dmau witness, Genz’s gakož and from tentíž gestures gehož name and status indicates vlastnoručnjm sign to confirm magi

Most of the words that I knew were incorrect were simply not translated yet. I used contextual clues for a few of them, like “gestures” and “magi.” Yes, those are real words. No, they are not likely to be found in this section of a parish register.

Honestly, the real benefit of this step by step exercise is to explain the process of transcription and translation to others; having seen many, many, many Czech records, often without this subheading, I already have a lot of background contextual knowledge about the meaning of this text. But the process is the same, regardless of the text. Maybe you will be able to apply the same principles from this blog post to other Czech documents that are not in a columnar format – land records, for example.

I quickly noticed that almost all of the words that stood out as incorrect had the letters j, ý, y, i, í, and g in common.

křtěcj

přiyměni

djtěte

přihlassuge

břjti

přjtomností

dmau

Genz’s

gakož

tentíž

gestures

gehož

vlastnoručnjm

magi

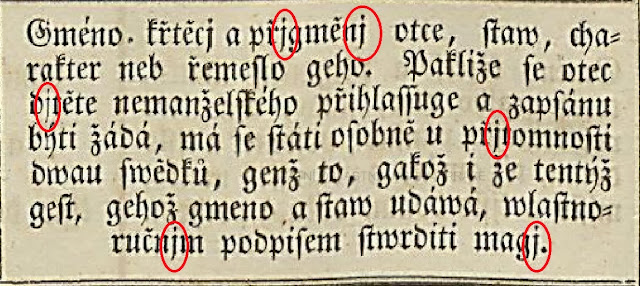

The first step in decoding a text is to find all of the similarly shaped letters. What stood out to me immediately was the letter “g”. Czech doesn’t use a lot of beginning g’s. Plus, I was positive that “magi” was not a word in this text. I found all of the letters in the text that looked like a g to me.

Then, I found the word that I already knew. “Přijmení” is Czech for “surname.” This clue lead me to plug in the letter j in the places where I had previously put g’s.

My text became:

Jméno. křtěcj a přijměni otce, stav, charakter neb řemeslo jeho. Paklíže se otec djtěte nemanželského přihlassuje a zapsánu břjti žádá, má se státí osobně u přjtomností dmau svědku, jenž to, jakož í že tentíž jest, jehož jmeno a stav udává, vlastnoručnjm podpísem stvrdítí maji.

The translation became:

Name. křtěcj and Father’s name, status, because the nature of his craft. IF the father of an illegitimate djtěte přihlassuje a registered břjti asks the person is standing at přjtomností dmau witness that this, and that is tentíž, whose name and condition indicates vlastnoručnjm sign to confirm they have.

I knew that j and i are often interchanged.

I tried substituting the following words:

křtěcj –> křtěci

djtěte –> ditěte

břjti –> břiti

přjtomností –> přitomností

tentíž –> tentíž

vlastnoručnjm –> vlastnoručnim

The translation became:

Name . křtěci and Father’s name , status, because the nature of his craft . IF the father of a child born out of wedlock přihlassuje a registered Brit asks , is the person standing in the presence of witnesses dmau that it , and that is tentíž , whose name and condition indicates a handwritten sign to confirm they have.

Making some progress! From a previous transcription project, I noticed that two s’s together like this: “ss” was a different way of writing š. I made this change:

přihlassuje –> přihlašuje

Then, I noticed two instances of a letter I had never seen before.

It sort of looks like an n, but also a j or a y. I tried several combinations, until ý gave me the following translation:

Name. křtěci and Father’s name, status, because the nature of his craft. IF the father of a child born out of wedlock and logs requests be registered, it shall become personally dmau in the presence of witnesses, who this, and that is the same, whose name and condition indicates a handwritten sign to confirm they have.

For “dmau”, I guessed, “dvau”. It turned out that “dva” is the Czech word for “two.” That final “u” was probably some kind of case ending.

I knew that it was two, though, because every time the fathers of illegitimate children are recorded, they must have two witnesses attest to the fact that they are really the father.

And…for the first one…I cheated. Google translate suggested křtíci for křtěci. This would mean “Christian name” – or given name.

So my final google translation turned out something like:

Name. baptizing and surname of the father, the state, because the nature of his craft. But if the father of a child born out of wedlock and logs requests be registered, it shall become personally by the presence of two witnesses, who this, and that is the same, whose name and condition indicates a handwritten sign to confirm they have.

Then I cleaned up the grammar a little bit.

Christian name and Surname of the father, his condition [married, unmarried], and the nature of his work. If the father of a child born out of wedlock requests to be registered, his identity shall become logged in the presence of two witnesses, that he is the same, and their handwritten signature and condition [or job] shall confirm they have [witnessed it].

Well, it might not be a perfect translation. But all of the ideas are clearly there. First name, last name, marital status, job title. The identity of the father of the child born out of wedlock confirmed by two witnesses, their titles, and their handwritten signatures.